by Giovanni Marenda (other articles in English)

This photo, published on 15 October by Greek minister Notis Mitarachis on his Twitter account, went around the web in a few hours and triggered a diplomatic crisis between Greece and Turkey. In the tweet, Mitarachis called Turkey a ‘shame for civilisation’, accusing Turkish authorities of leading 92 people to the northern Greek-Turkish border, forcing them to cross the Evros river naked – allegedly after robbing and beating them.

The Greek Minister of Migration and Asylum also announced that he had already reported the case to the European Commission and would bring the matter to the attention of the UN during his upcoming visit to New York. A few hours later, the UN expressed its deep distress through the UNHCR agency and demanded ‘a full investigation into this incident’.

Of course, Turkey immediately returned the accusations to the sender, reversing the narrative: ‘We urge Greece to abandon its harsh treatment of refugees as soon as possible, to cease its baseless and false charges against Türkiye,’ wrote President Erdoğan’s top aide, Fahrettin Altun. And again: ‘With these futile and ridiculous efforts, Greece has shown once again to the entire world that it does not respect the dignity of refugees by posting these oppressed people’s pictures it has deported after extorting their personal possessions.’

This is not the first time that the age-old rivalry between Athens and Ankara has occupied the field of the treatment of migrants at the border, with mutual accusations of incivility and calls for respect for human rights. This conflict, which takes place in the sphere of media representation, becomes increasingly grotesque and contradictory in light of the systematic violence on both sides.

In fact, according to data collected by Aegean Boat Report, in the first nine months of 2022 Greece turned back more than 18,000 people at the sea border. Many of them had already landed on the Greek islands, being arrested, robbed and tortured by the Hellenic police before being released at sea, sometimes without life jackets and with their hands tied, according to some testimonies.

At the same time, the land border along the Evros river between Greece and Turkey, is perhaps the most militarised frontier area in Europe, inaccessible to activists and journalists, scene of daily push-backs and violence of all kinds. The stories of people abandoned by the Greek authorities in the islets of the river, without water or food for days, follow one another, like that of the Syrian girl who died from a scorpion bite. And the stories of those who cross the Balkans tell of detention in unknown places, of torture with electric shocks, of beatings to death, of dogs trained to bite.

Migrants are forced to walk for days in the darkness of night and woods to avoid Greek commandos, until they reach Macedonia and Serbia, in terror of being spotted by the police or locals. Moreover, Lighthouse Report’s recent investigation showed how Greek police exploit asylum seekers themselves to carry out violent refoulement operations. All of this with the complicity of Frontex, as denounced (paradoxically) by Erdoğan’s own aide, Fahrettin Altun, but above all by the Olaf report recently made public by Der Spiegel, which a few months ago led to the resignation of director Fabrice Leggeri.

In Turkey, meanwhile, government deportation programmes are now fully implemented. The Human Rights Watch report 1 – based on dozens of interviews with Syrian deportees – recounts police raids on factories and neighbourhoods, arbitrary arrests of people despite their temporary protection permit (Turkey applies the Geneva Convention only to European citizens), detentions in pre-repatriation centres, places of physical and psychological violence financed with European money, such as the one of Tuzla, Istanbul. Finally, the journeys in handcuffs to the border crossings of Öncüpınar/Bab al-Salam or Cilvegözü/Bab al-Hawa, and the crossings of the frontier at gunpoint, not before having voluntarily signed the repatriation papers under blackmail.

According to data from the local authorities, between February and August 2022, 11,645 people were repatriated from Bab al-Hawa and 8,404 from Bab al-Salam, but there are certainly many more. The deportations take place to territories in north-east Syria, under the control of Turkish militias or directly backed by Turkey, with the clear aim of ‘de-Kurdising’ the area. For people, it is not even possible to return to their home town afterwards, due to the instability in northern Syria and the lack of safety. Indeed, in addition to being a country destroyed by ten years of war and still plagued by armed conflicts, Bashar al-Assad’s return to power puts those who fought in the anti-government forces or who simply fled once the conflict broke out at great risk.

The lives of migrant people in Turkey – which hosts 3.6 million Syrian refugees – are severely challenged not only by the constant threat of deportation (even for non-Syrians: Erdoğan has an extensive network of bilateral agreements with African countries, for example), but also by labour exploitation, inflation, and the growing spiral of racism, fuelled by the electoral climate towards the presidential elections of June 2023. In fact, street assaults by private citizens, often extreme right-wing militants, on people of Syrian origin – who have sometimes lived and worked in the country for almost ten years -, have become the norm, especially in working-class neighbourhoods of large cities, to the point of cold-blooded murders on racial grounds.

Among non-Turks, there is the fear of being heard speaking Arabic, of being reported to the police by their landlord or neighbours. Moreover, most people formally live in violation of the geographical restriction prescribed by temporary protection, thus being constantly blackmailed and liable to deportation. This restriction prevents people from leaving their assigned province and is therefore forcibly ignored, as it would prevent them from living in the main centres, where it may still be possible to find a home and a job. In fact, as of February 2022, 16 provinces are banned from registering the residence of those seeking protection, including Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir, and refugees are thus restricted to the most isolated and peripheral regions.

The most farcical aspect of the mutual accusations between Greece and Turkey, however, is the Greek government’s Joint Ministerial Decision (JMD) dated 7 June 2021, by which Greece declared Turkey a ‘safe third country’ for protection seekers from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Syria, Somalia and Bangladesh.

As reported by the Greek Council For Refugees, these five nationalities accounted for 67 per cent of the asylum-seeking population in Greece and over 60 per cent of the refugee population, with an acceptance rate of 76 per cent to 95 per cent. As Equal Rights Beyond Borders pointed out, the ministerial decision was based on an ‘opinion’ issued by the director of the Greek asylum service, certainly not legally sufficient, yet fully in line with European policies of refoulement and relocation to external countries.

In fact, already with the 2016 EU-Turkey agreement, a mechanism for the admission of asylum applications reserved for Syrian refugees was established, thus providing for the possibility of not admitting asylum applications and expelling the applicant before the actual analysis of the application. At the time, the European Commission had justified the legal criticality of this measure by the emergency circumstances, effectively indicating the direction that national and European policies would consolidate in the following years, within the framework of the European Pact for Migration and Asylum.

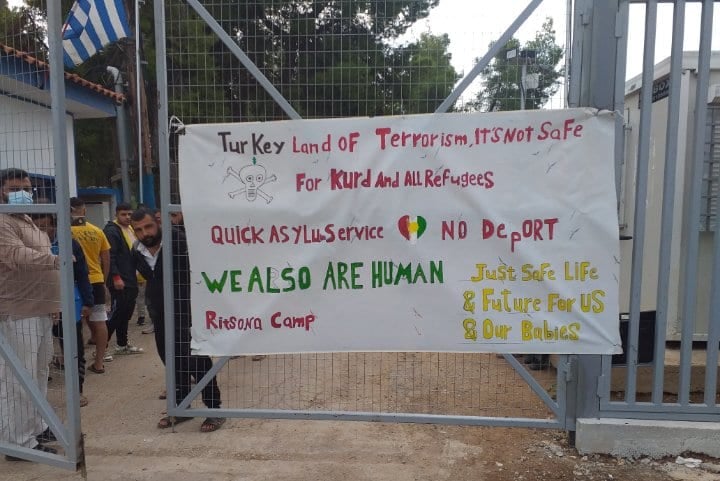

To date, for the five nationalities mentioned, all interviews conducted by the Greek authorities in the reception and identification centres on the islands and on the mainland only concern the living conditions in Turkey and the Greek-Turkish border crossing, according to the Fast Track Border Procedure. People are explicitly prevented from talking about the country of origin, the rest of the journey, the real reason for the asylum claim. The aim is to make legal what is already being done on a large scale with informal push-backs, yet the rainfall of inadmissibilities (in 2021 they increased by 126%) has so far not been matched by any transfer to Turkey. In fact, since March 2020, the Anatolian country has not accepted returns from Greece, and has officially asked the Greek government to withdraw its decision. Thus, people find themselves in a legal and existential limbo: inadmissible from Turkey, unacceptable and illegalised in Greece.

One year after Turkey’s designation as a safe country, a petition 2 signed by many NGOs was launched, calling on the Greek government to revoke the decision, defining it with three adjectives: unlawful, inhuman, unworkable. Unlawful because it has no legal basis, being based on a contradictory and insufficient opinion. Inhuman because Turkey does not guarantee full protection under the 1951 Geneva Convention, does not apply the principle of non-refoulement, has withdrawn from the 2014 Istanbul Convention on violence against women, has no independent judiciary, persecutes ethnic and religious minorities, LGBTQI+ communities, political opponents and human rights defenders. Unworkable because readmissions are not in fact possible, thus keeping people in a limbo of uncertainty, suffering, exploitation, without access to basic services.

For the Greek government, then, is Turkey a ‘shame of civilisation’ or a safe country? It is a game of sides played on people’s skin, of mutual accusations of fake news in the face of evidence and hypocritical calls for welcome and human rights. Whether it is the Greek or Turkish police who beat and denude at the border, it makes little difference. We know they both do it anyway.