by Pietro Desideri, volunteer onboard the Nadir

«Crack» stems from my experiences and emotions aboard the sailing ship Nadir, as a volunteer with the German association RESQSHIP, during a monitoring, search and rescue mission. It is a five segments story that comes out every Wednesday in November, starting on 2.11.2022: an infamous day for the renewal of the agreements between Italy and Libya. «Crack» is part of what I would like to say to Fortress Europe 1.

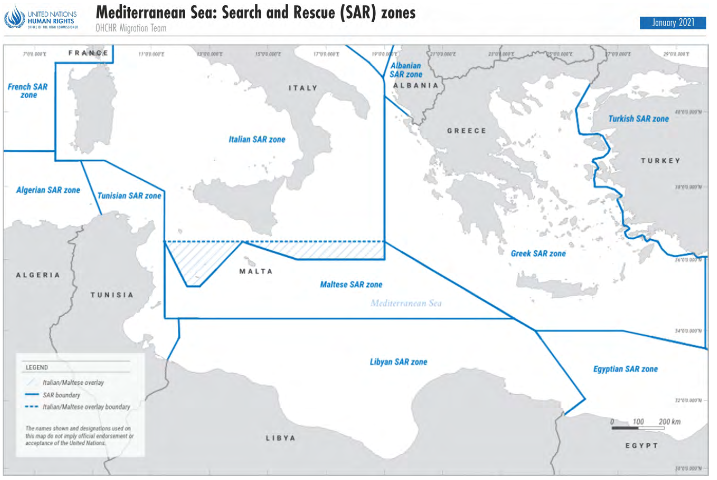

Our mission lasted 21 days, 15 of which we spent at sea. We rescued about 110 people from three different boats. In this article I write about the geographic, administrative and political reality that served as the backdrop for all our operations: the SAR area. I also tell some of its contradictions through the lenses of our first rescue.

It is the seventh day of sailing. I am on the bow, tinkering with some rope when I hear on radio channel 16 an alert. It is (presumably) a Tunisian fishing vessel that has spotted a boat in distress. A chain mechanism is ignited, which roughly looks like: heart thumping, concentration, stop doing whatever I am doing and go towards the radio, find paper and pencil, turn on the recorder.

The alert we hear is spoken in a mixture of Italian and French, marked by repeated key words “bateau, bateau,” “clandestino“; the tone is animated but not chaotic. It comes the answer from Lampedusa port authorities: “I understand, you have to wait.” Then again, “you have to wait.” They speak Italian and I translate for Johannes, our skipper (captain). We gather pieces of information that make us almost feel hopeful: the communication is functional, Lampedusa is alerted, they must be already preparing to coordinate a response. Instead we then hear that “we have forwarded the request to the relevant authorities” and realize that there will be no support. We head towards the coordinates the fishing boat has indicated, without sparing the engine.

SAR stands for Search and Rescue and refers to the activities that must be carried out when a vessel is in distress. International maritime law, particularly through the 1979 International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue, makes it clear that during a distress case the competent SAR states must take urgent action to ensure the necessary assistance. The coordinates we heard over the radio situated the vessel in the Maltese SAR zone, so it is Malta’s responsibility to coordinate rescue operations.

The first short-circuit of the SAR in the central Mediterranean is that often boats in distress are in the Maltese SAR area, but they are much closer to Lampedusa. Therefore, it would be natural for Italian authorities to coordinate rescue operations. Instead, Italy in most cases objects that Maltese authorities are responsible and bounces requests back to Malta.

This flaw in the SAR is actually a sinkhole because it intersects with Malta’s abdication of responsibility. With disarming simplicity, Malta does not answer to distress alarms. After a while we become desensitized towards what is in fact a serious violation of international maritime law. As I metabolized it, civil fleet vessels, including the Nadir, now forward mayday relays and requests to Malta to coordinate rescue operations not so much because they hope to find support, but out of unilateral respect of the law.

To summarize what often happens when a civil fleet vessel finds one in distress: 1. Malta ignores the requests for support, 2. Italy is then solicited for support 3. Italy answers it has no jurisdiction or that it has forwarded the request to the relevant authorities, the Maltese ones. It can go on in frustrating loops, who is losing out always are the people who are risking their lives.

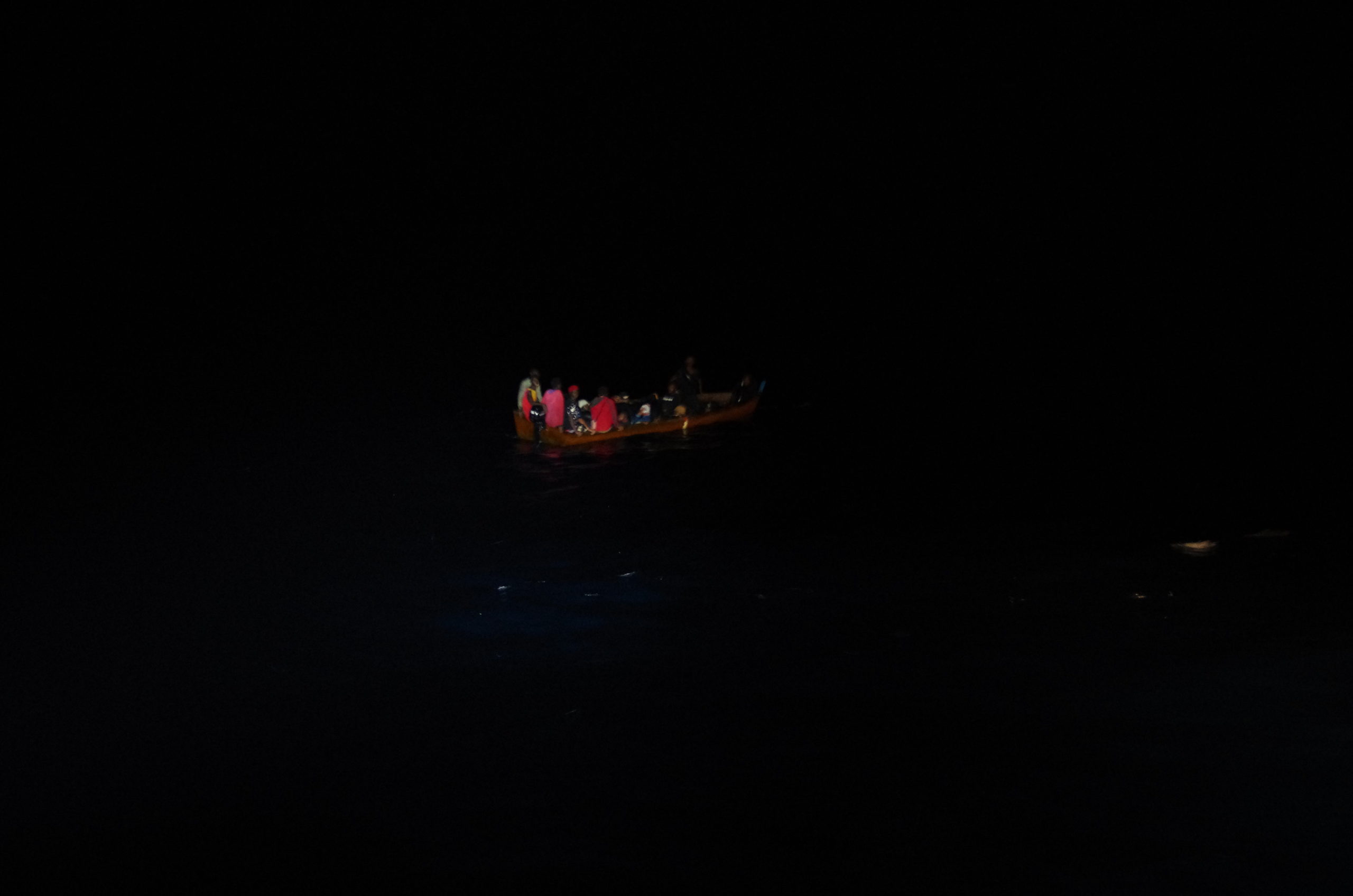

At sea, distances are magnified by the slowness at which boats proceed, due to the friction of the water. The Nadir, for example, rarely goes faster than 8 knots, 15 kilometers per hour. It takes us about 8 hours to reach the point where we finally find the boat, with the engine not running and 34 people on board. Keeping a safety distance, we approach, I take the megaphone and start speaking.

“We are friends, we come from Europe. We will help you. Please remain seated, so your boat will be more stable,” I say in French. Before the mission I was afraid that the communication I was responsible for would not work, that I would not be up to the task. I could not project myself into the situation, despite the training. Instead as I speak a part of me feels relief that it is working, not only we are able to exchange information, but also to collaborate effectively.

The first contact has two main objectives: to establish the communication channel and to perform an overall assessment, especially on any potential serious medical issues, on the engine, and on the general conditions of the boat. It is night, we direct a beam of light to see them. I feel ashamed to flash and scrutinize them. I’m not even sure why, perhaps I feel the weight of the injustice that I have a red passport while they try to get to Europe as they are trying.

The boat contains too many people in too narrow a space. The water line is high for the weight of those on board. There are no serious medical emergencies, however, and it seems that the reason the engine is not working is the lack of fuel. It hurts, but we decide that if possible they will continue the journey on their boat. We will give them a can of gasoline and escort them closely, all the way to Lampedusa, ready to intervene if needed.

As I illuminate them with a flashlight to maintain visual contact, I think about the collective, social failure we are experiencing. I just want to take them on board. And I am sure it is the same for each of us. Abbi tells me, “It’s very difficult for me, as a doctor, not to bring help immediately.” Yet the political situation does not allow us to do so. In fact, states not only do not help during distress calls-Malta not responding, Italy bouncing back to Malta, etc.-but they are also active obstacles. Often, when a civil fleet vessel attempts to disembark people at a safe port, authorities deny access. Or they impose days and days of waiting. Indeed, the policy of “closed ports,” now infamously back to full swing, coexists with the less apparent policy of administrative and bureaucratic swamps. We do not want to risk seeing the Nadir stranded indefinitely, waiting for the assignment of a safe port where rescued people can be disembarked, thus leaving the central Mediterranean even less patrolled.

We continue to slowly escort the boat for about an hour, until the conditions worsen, a person needs medical attention. We evacuate her, along with the women and a little girl. We ask the men to stay on board, and they respond with full cooperation. It sounds absurd, but it is all so real: the men still on the boat proceed at the speed their engine allows, 2 knots, not even 5km per hour, then the engine gives out completely. For the third time, we have to decide to leave them in their boat, even though they are now without propulsion. We hand them a rope and begin to tow them. By now it is morning, and as we proceed toward Lampedusa, I hear them singing. They are happy that this is all coming to an end.

Charlie Papa 319, the Italian Coast Guard, is alerted, they come to meet us near that imaginary line that demarcates the Italian SAR zone, within which they can no longer reply “we have forwarded the request to the relevant authorities.” When we finish the transshipment of people and I see them leaving on board Charlie Papa, they say goodbye to us. I think back to the people rescued. The next article is about them.