Rethinking Resistance towards 25th April

“Don’t forget the refugees and support us. Not with money. But stand with us. This is a message from Lesbos” that was how Raid, from Moria White Helmets, wished me goodbye. I interviewed him and, separately, Noemi, co-founder of Now You See Me Moria, and we have exchanged on how effective European solidarity should put people on the move and their struggle front and center of the conversation.

In the past years the island of Lesbos has turned into a lab for migration and carceral policies. The infamous Moria camp, burned to the ground in 2020, epitomized the worst of how the European Union could treat people who claimed asylum. Reacting to this system of institutionalized racism, different strains of European solidarity emerged on Lesbos. Unfortunately, the one that imposed itself was the charity approach of cynically representing refugees and asylum seekers as completely helpless, desperate, and needy of the services that each NGO was willing to offer.

I wanted to interview Moria White Helmets and Now You See Me Moria projects because they both set the example for a completely different paradigm of how European societies could be supporting refugees. They both have the word “Moria” in the name, even if the camp does not exist anymore. That is a conscious choice since Moria has come to symbolize an archetypal place of oppression, one where the systems of borders and racism materialize. A place resisted and opposed by the people it tries to trap, where the calendar is always fixed on the same date: 25th April.

Raid tells me how the Moria White Helmets was born in March 2020, in Moria camp from a group of refugees, including himself. The group was trying to react to three different pressures. The first was the horrible inadequacy of the camp where they lived -at the time, it was hosting well over 20.000 people instead of the 2.800 it was designed for. “It was horrible” Raid sums up. The second was that NGOs, that were indeed providing important services, suspended their operations as they started to being attacked by local fascists. Thus, refugees were left without lifeline support overnight. The third was the pandemic, which the group wanted to counter in the absence of any institutional support. They started by spreading Covid-19 awareness messaging and collecting waste inside the camp, reaching up to 250 volunteers and becoming one of the most reliable service providers, completely community based.

Right now, Moria White Helmets is organizing a huge amount of activities in Mavrovouni camp (the camp that substituted Moria after the fire). Those include: garbage collection, recycling, carpentry, barber shop, beauty salon, bicycle repair, education classes, electricity. It was simply mind blowing to hear Raid talk about the array of activities they do.

Now You See Me Moria was born, and still is, as an advocacy platform for refugees and asylum seekers, from where they could directly interface with the European public and denounce reception conditions. It started from the realization that the production of knowledge and visual culture relating to refugee issues was operated by European photographers, politicians, journalists, etc.: never by refugees themselves.

Noemi reminds me how any Google search with “refugee” or “migrant” as keywords, even nowadays, just proves how much our culture has construed a stereotypical image for a refugee, as extremely vulnerable and desperate.

Noemi connected on Facebook with Amir, a person seeking asylum who was posting on his Facebook wall evidence of the indecent reception conditions. They started the project together, on Instagram. The profile now vehicles the grievances and requests of the refugee and asylum seekers community: people directly reach out and post their own content, through which they denounce that the food they received is inedible, that their children live behind fences and are missing school, that the system is creating psychological trauma, and more.

The two projects operate independently from each other. Though, while exchanging with Noemi and Raid, it was clear that they shared a common understanding of what solidarity looks like compared to the work of most NGOs on the island, and that they have similar views on how the current reception system is failing asylum seekers and refugees. Instead, the relation that the two associations have with the authorities is different.

When they relate with officials, both projects face a structural issue, that they do not have an official status or recognition, nor certificates, notwithstanding that they are widely credited for being some of the most authentic and connected-to-refugees associations. However, Moria White Helmets entertains a good working relation with local authorities. For example, they cooperate with the electrical department in the camp. Now You See Me Moria, instead, is in direct conflict with authorities. Mavrovouni camp is a semi-closed one, where it is difficult for people from the outside to enter and document, and where residents’ mobility is restricted (for example, by a curfew).

In this context, the work of documenting and denouncing of Now You See Me Moria is all the more important, and targeted by the authorities. The project gives the power to refugees to become journalists/activists of their own situation, and they do so even if they face criminalization and retaliation from officials. Noemi reminds me that authorities have made it illegal to take pictures inside the camp, meaning a person cannot take a picture of the house where they live, and that there have been cases of harassment with phones confiscated and destroyed.

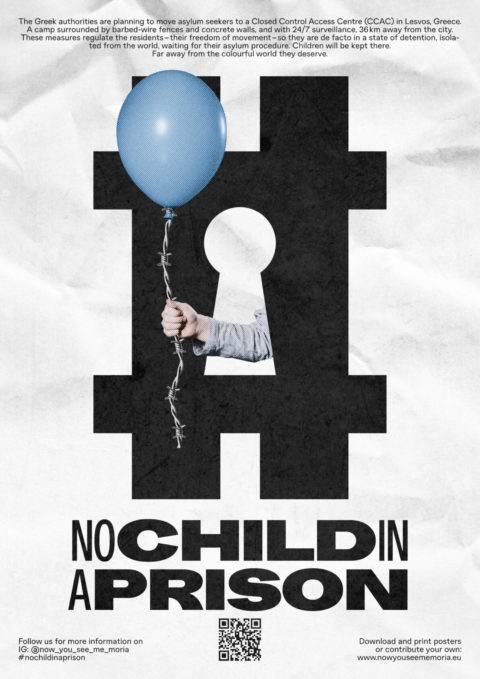

Both projects regard extremely negatively the ongoing finalization of a closed facility in Lesbos, Vastria. This is part of the construction of 5 CCAC: Closed Controlled Access Centers. Funded by the European Union (which always likes credits). The combined costs for the five CCAC, when completed, is 260 million of euros, and they are built on average 14 km away from the closest inhabited center 1. Vastria camp will be 36 km away from the closest village, it is built in forest which is highly prone to fires, and will use high technology surveillance systems to control people. The word that both Raid and Noemi use to describe it is uncompromising: “prison”. Now You See Me Moria supports a campaign, “No child in a prison”, which strives to raise awareness within the European audience about this ultimate segregation project. Raid mentions that there is unanimity within the refugee community that they are strongly opposed to Vastria.

Models of solidarity are the next topic of our conversations. There is not much solidarity to talk about on the government side, since the state has sorely failed in providing even the most essential services. Food, for example: Now You See Me Moria documents well how Elaitis, the food catering company contracted by the government, delivers daily thousands of inedible servings (the project also argues that only widespread corruption can account for those shortcomings). Instead, we drive our exchanges into how NGOs, especially the big ones, operate in the gaps left by the institutions, in the name of “solidarity” with refugees and asylum seekers. Both Noemi and Raid portray those actors with a critical eye, to the point that sometimes they group them with more official stakeholders like UN actors or even state authorities.

For example, Raid mentions that many aid actors are wasteful, because they “invent difficult solutions, we have simple, effective solutions”. He mentions language classes, that Moria White Helmets organizes twice a day, six days a week, and prove much more attended by than the UNICEF ’ones. Those are in the city, far away, while people prefer to attend language classes nearby and be taught by a member of their own community. They also mention the many costs that big organizations incur (either called indirect costs or infrastructure costs) – all money that does not go where it is supposed to.

However, the most fundamental criticism that both projects move against most NGOs is that they outright compound to current issues, because the act of bringing humanitarian aid is not a neutral one. It can degrade the agency of people who are very much able to support themselves, if only given the chance. That does have consequences on individual’s wellbeing, since passively receiving support impacts on one’s mental health.

Many NGOs, they argue, follow a well-known cycle: fly well-intentioned international volunteers, make them do jobs that refugees and asylum seekers could do themselves (like digging or cleaning clothes), take the pictures of smiling (or crying) children and the donations money that follows. This cycle sustains a machine which is effectively a business, with executives sitting in European offices, intermittingly taking flights to “come to the field”, and come back.

In contrast, Now You See Me Moria has decided to leave to refugees and asylum seekers the right of self-representation and has set almost no rules, but the one on faces of children. Those should never appear, Noemi states, to protect their privacy, their agency in the future and respect their right of not being exploited for fundraising. Likewise, Raid clarifies that Moria White Helmets is not against international solidarity, on the contrary “we like volunteers”. But he challenges a system of hierarchy where internationals do petty jobs which supposedly support refugees. He would prefer a peer-to-peer relation where people “come, eat, drink, share with us”.

“Aid” must come from within, from refugee and asylum seekers communities themselves – that has been the leitmotiv of our conversations. Both projects stressed that the reception system should reinforce mutualism and self-organizing of refugees, the contrary of what it is going on now. Exchanging with Moria White Helmets allowed me to realize that not only the association was bringing services in the most effective way where it was most needed, respecting the agency and wishes of the community involved. It was also bringing services to the other residents on the island, shifting the model of aid. For example, cleaners from the project support the Municipality with garbage collection outside the camp once a week. They also work with teachers in municipal schools to encourage pupils to recycle, a huge issue for Greece. And all their services are open and free for anybody, not only refugees. That is how the barber shop is used by the official cleaners or guards of the camp as well.

Now You See Me Moria supports the same analysis. Noemi makes the point that an effective way to receive people in the European Union is to restore their autonomy, which is a foundational human right: if you do not have it, you can scarcely enjoy the others. She goes against a system that “wishes to control” people, “annulling” them. Just like Raid, Noemi does not ask for donations. She mentions that change will not come from politics, but only from society, and that the reason why we have closed camps in Europe -prisons- is that European societies came to accept them. Her call to action is grounded and hopeful: any individual has the possibility to go against this system, any initiative, big or small, is a space of opportunity and resistance.