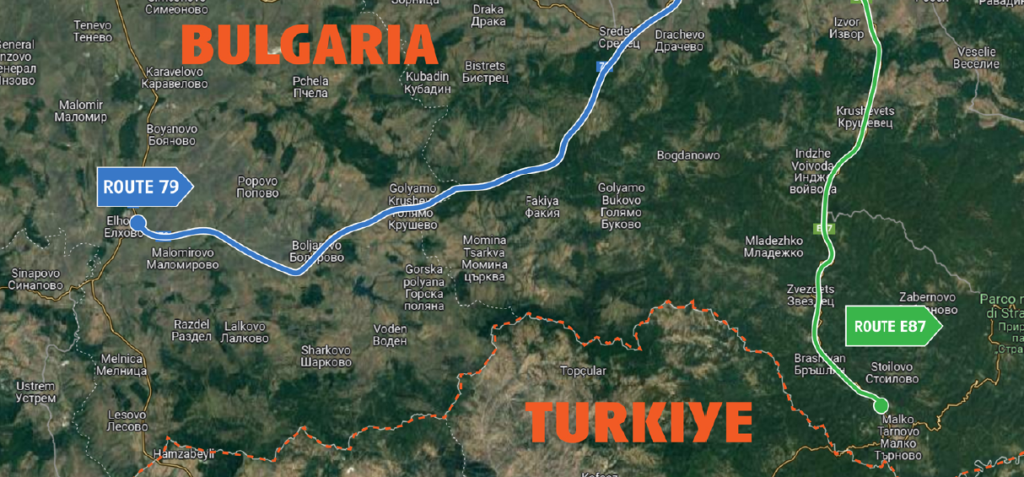

‘ГРАНИЦИТЕ УБИВАТ’, ‘Borders kill’. This inscription stands out on rusty old cisterns along road 79, the road from Elhovo to Burgas, that follow the Bulgarian-Turkish border until the Black Sea. We of the Collettivo Rotte Balcaniche made it, as red as the blood we saw flowing in these hills. We wanted to imprint in the physical space a trace of those who lived their last moments in these very woods, to leave a mark to give to memory a material dimension. On the other hand, we wanted to launch a warning, to speak to the people who continue to pass by on this road, ignoring its stench of death, and to those who are directly responsible for it, to say ‘we know and we will not forget’. The result is a simple inscription that perhaps few will notice. It encompasses the tears that accompany memories and a scream that rises within, love and anger.

Since last year, the Bulgarian-Turkish border has once again become Europe’s first land gateway. Indeed, the data released by the Bulgarian Border Police count over 158 thousand attempts to enter the territory illegally prevented in the first nine months of 2023, compared to 115 thousand in the corresponding period of 2022, when the same statistics had already more than tripled 1. The movement of people changes according to border policies, like a stream of water searching for an opening, so the total militarisation of the Greek-Turkish land border, which runs along the Evros river, has shifted migration routes towards the more porous Bulgarian border. On the other hand, Erdogan’s increasingly aggressive deportation policy – which has already forcibly relocated 600,000 Syrian refugees in the Turkish-controlled northwest of the country and promises to reach the one million mark soon – forces the more than three million Syrians living in Turkey to move to safer places.

We started to learn about Bulgarian police violence more than a year ago, not in journalistic investigations but in the stories of migrant people we met in Serbia, while we were involved in distributing food and hot showers to those who were beaten up and pushed back by Hungarian border guards. We are a group of solidarians who started travelling along the Balkan routes in 2018 to actively support people on the move, and we haven’t stopped since. Although we have grown over time, we remain a self-organised collective without any formal recognition. Precisely for this reason, we have decided to move towards the contexts characterised by greater repression, where more institutional actors struggle to find viability and solidarity practices take on a conflictual and political value. One of our goals is to be the anti-border, building safe routes across borders, underground railways. However, we would never have thought of becoming a ‘rescue team’, searching for and rescuing missing persons – dead and alive – in the forests of Bulgaria.

The first rescue operation we came across was during the night of 19-20 July. I was about to go to sleep, around one o’clock, when I heard the Collective’s phone ring insistently – the phone through which we handle requests for help from people living in refugee camps in the southern region of Bulgaria 2. It was M, a Syrian man living in the Harmanli camp, whom I had met a few days earlier. ‘There is a pregnant woman on route 79, we need an ambulance’. With her, his two little girls aged three and six. We call 112, the unified emergency number, after informing her that the police would probably arrive before the ambulance, and we couldn’t know what would happen. After realising that the operator was lying to us, insinuating that the rescue teams had left without having found anyone at the coordinates we had reported, we decided to take action ourselves. Since then, there have been more and less intense weeks of going out and searching. We have a database of the forty or so cases we have dealt with in various ways between the end of July and mid-October: names, stories and photos that nobody would want to see. In the past three months, a network of associations with whom we collaborate in emergency management has also developed, including in particular CRG (Consolidated Rescue Group), a group of Syrian volunteers who do an incredible job of collecting reports of ‘distress’ and ‘missing people’ on the borders of Europe, as well as liaising with the family members.

Reconstructing this type of situation is always complicated: information is fragmented, the chronology of events uncertain, the intervention of the authorities unpredictable. We often find ourselves assembling pieces of a puzzle that do not fit together. It is the migrants themselves who launch the SOS, or, if they do not have a phone or it is dead, the ‘guides’ 3 who accompany them on the journey. The requests contain the person’s personal data, contact details and state of health. Families then contact solidarity organisations such as CRG, which is a trusted reference among Syrian people. The only thing we can do – but that nobody else does – is to ‘put our bodies on it’, to stand between the police and the people on the move. The fact that there are white, European persons at the scene of the emergency forces the emergency services to arrive, and discourages the police from pushing back and torturing. In fact, it is the hierarchy of bodies that determines how ‘saveable’ a person is, and migrant lives are worth less than zero. On the night of 5 August, on our way to retrieve H’s corpse, we are stopped by a dark van with no police insignia. It is a patrol of the army’s special corps for capture and refoulement. We tell them the truth: we are going to look for a dead boy in the woods, we have already notified 112. One of the soldiers wants proof, so we show him the photo taken by his companions. Seeing the corpse, he laughs, ‘it’s funny’, he says.

Every road is a dead end that leads to the border police, who have no interest in saving lives but only in incriminating those who save them. Should we call 112 immediately, accepting the risk that the police may arrive before us and turn people back to Turkey, leaving them naked and wounded in the border woods, and then be forced to try that deadly journey again or imprisoned and deported to Syria? Or not calling 112, thus losing that shred of chance that an ambulance might actually, sooner or later, arrive and potentially save a life? The moment of intervention poses impossible questions every time, revealing the power asymmetry between us and the authorities, whose moves we cannot predict. Some changes, however, we have also consistently observed in the behaviour of the police. While our actions initially succeeded several times in avoiding the negligence of the authorities, saving people who would otherwise have simply been left to die, in the last month our searches have almost always gone in vain. This is because the police arrive at the coordinates before us, even when we don’t warn them, or intercept us along the way, preventing us from continuing. These are probably not casualties, but they are controlling our movements, to try to take away this space of action that we had illusions of having conquered.

However, we know that the cases we have intercepted are only part of the total. The reports that arrive through CRG almost exclusively concern people of Syrian origin, while we have rarely received requests from other nationalities, which we know are present. Moreover, Dr Mileva, head of department at the Burgas morgue, says that almost every day a corpse arrives, ‘most are full of worms, some have been eaten by wild animals’. They no longer know where to put them, the cold storage rooms are full of unidentified bodies, but the families do not have the possibility of coming to Bulgaria to start the recognition, repatriation and burial procedures. In fact, it is impossible to get a visa to come to Europe, not even to recognise a child – and it is impossible to move even from other European countries if you are an asylum seeker. Alternatively, you need money for a lawyer and to take a DNA test through the embassy. Bureaucratic procedures know no mercy. The politics of the border act as much on the living body as on the dead one, thus on the possibility of mourning, of simply having the certainty of having lost a sister, a mother, a brother. Just to know whether to mourn. Death is also a social conquest.

‘I have been a troubled sister for 11 months. I no longer sleep at night and only spend quiet days on sedatives and depression pills. Wherever I have asked for help, I have remained without answers. I ask you, if it is possible, to take me by the hand, if money is needed, I am ready to go into debt to find my brother and save my old mother from this slow death.’ So writes S, from Sweden. His brother was 30 years old. He had fled Afghanistan after the return of the Taliban because he worked for the American army. He had left Turkey to head for Bulgaria on 21 September 2022, but on the 25th he was no longer able to continue the journey because of pain in his legs. In a video, the smugglers who led the journey explained that they would leave him at a certain point, near route 79, and that after resting he would have to turn himself in to the police. Since then the trail of him has been lost. He was not found in the forest, nor in the refugee camps, nor among the bodies in the morgue. He has been swallowed up by the border. S sends us the names, photos and dates of disappearance of 14 other people, almost all Afghans, who disappeared last year. She is in contact with all the families. We have no answers either: the older the report, the harder it is to do anything. We know that the most likely thing is that the bodies have rotted in the underwood, but what to say to the family members who still hold on to irrational hope? We now walk on the bones of those who came before, and there they remained.

- РЕЗУЛТАТИ ОТ ДЕЙНОСТТА НА МВР ПРЕЗ 2022 г., Противодействие на миграционния натиск и граничен контрол (Results of the Ministry of the Interior’s activities in 2022, Countering migratory pressure and border control), p. 14

- As far as asylum seekers are concerned, the Bulgarian ‘reception’ system is managed by the government agency SAR, and consists of the ROC (Registration and Reception Centre) camps in Voenna Rampa (Sofia), Ovcha Kupel (Sofia), Vrajdebna (Sofia), Banya (Nova Zagora) and Harmanli, as well as the Pastrogor transit centre (located in the municipality of Svilengrad), where accelerated asylum procedures are carried out. […] There are two detention centres: Busmantsi and Lyubimets. For further information, the report written by the Collective is available.

- This is also what they call the smugglers who lead people on the journey on foot.