For more than a month now, as Collettivo Rotte Balcaniche Alto Vicentino we have been in Subotica, in northern Serbia, on the border with Hungary. Daily we cross the immense plains of the Danube valley, where the endless plane of sunflower and corn fields is pierced perpendicularly by the Hungarian barrier. Here the inherent unity of the landscape, stretched to the horizon and veined by the great rivers, is interrupted in the European barbed wires. Here the horizontal dimension of space breaks into the vertical dimension of power, which acts by placing borders, dividing and hierarchizing the equal. Mobilizing Deleuze and Guattari’s categories, borders are “striations” imposed by states (in this case unions of states) on a space that is itself “smooth,” devices of the spatial and social order.

Opposed to the geographies of the powerful, however, are the geographies of the oppressed, those travelers who have nothing to lose, those who migrate from south to north and east to west. These are dismissive geographies, continuous movement that challenges the static nature of the established order, dynamic force that opens cracks in the striations and thus in the (global) social relations, as petrified in inequality and exploitation.

The EU recalls of those enclaves of the rich typical of large metropolises, defended from view and assault by the poor in surrounding working-class neighborhoods by private security and ten-foot-high walls. Similarly, the European gated community defends itself on the borders, waging war on those who simply seek a worthy life, a safe place, better material conditions. The massive economic and technological means, and the brutality of the violence perpetrated, unveil the radical nature of what is at stake in Europe’s war on migrant people. It is the barricade of the European empire whose reproduction is endangered by the climatic and social collapse it caused, the fortification of Europe’s centuries-old dominance over Africa and the Middle East threatened by the multipolar global order, the strenuous defense of imagined national purities and white material privileges. The colonial essence of border and asylum policies lies in their being instruments of recruiting cheap labor, of controlling and selecting lives, of producing differences between bodies. There are bodies that can drown in silence, there are bodies that can be shot on sight on the borders, there are bodies that can be imprisoned in detention camps, there are bodies that can die in the plantation sun or be consumed for a few euros an hour in factories. And it is the Europeans who determine this possibility.

It is therefore not acceptable for these lives to self-determine by setting out, crossing borders without asking permission. For a system that wants to hetero-determine and profit the life of the planet in all its forms, migrant subjectivities are an element of disorder that must be eliminated: killed, rejected or disciplined and made functional to the needs of capital. That movement is a rupture of the (socio)spatial order that must be first punished and then reabsorbed – first the splendor of border torture, then the bodies indocilated by bureaucracy, confinement, exploitation, detention. Not only for those who are already here, but especially for those who may embark on the same journey in the future.

Because the capital knows no borders but cannot exist without them.

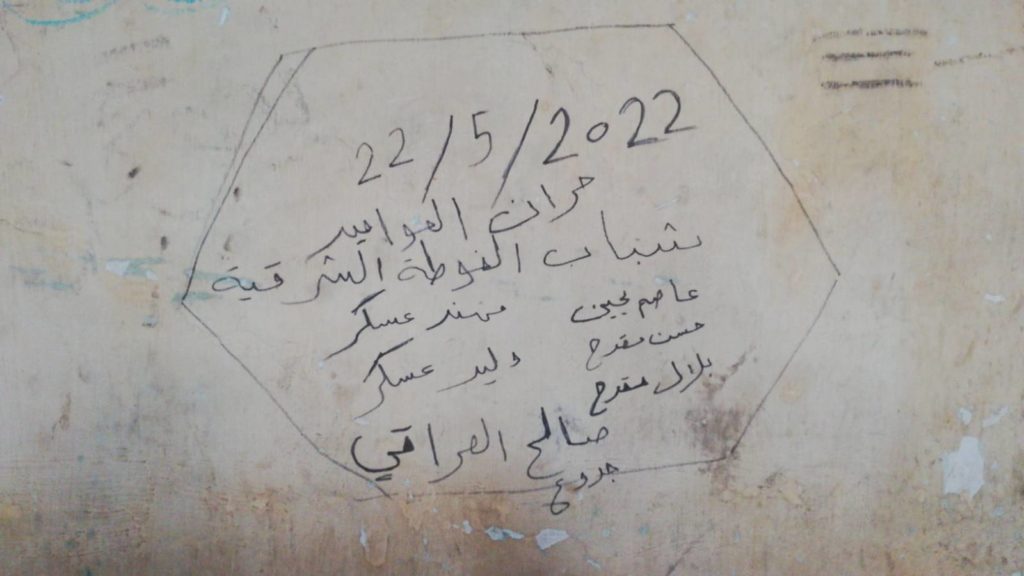

Engraved in the flesh of migrant people are the contradictions of the world of today and tomorrow. Bodies that are already archeologies of the present time, geological stratifications of the continuous and systemic violence that determines individual and collective biographies. The scars are the tortures in Assad’s prisons, the whippings of the Taliban, the blind violence of Daesh, Erdogan’s bombs on Rojava and Israel’s bombs on Palestine. And then the pincer marks used by Greek police to inflict electric shocks, the dog bites of Bulgarian police, the beatings of Romanian commandos, the bullets of Hungarian police, and the barbed wire-infected wounds. Malnutrition, scabies, feet ruined by too many miles walked. Few traces of the fleeting passage of travelers settle in places: cans of energy drinks, worn shoes, the remains of campfires. On the walls of occupied cottages are the names of the people who passed through inscribed with charcoal – perhaps the urgency to leave a small trace of themselves, to engrave in time and space a sign of their denied lives.

To date, the Serbian-Hungarian border is the hottest point on the northern Balkan routes. It is the last border: after that wall is Europe. “Meet you in Europe, Inshallah,” we hear from the people on the move we meet in the moment of greeting. Sometimes they also ask us what we are doing there, in the nowhere frequented only by them and the border police, when we could stay quietly in that much-desired Europe. And we wonder too, us who call ourselves solidarians, while we walk questioning, accompanied by a thousand doubts.

We ask this ourselves when we distribute food, knowing that it will not be enough, and that people will fight to grab the last piece of bread (which we, magnanimous and charitable Europeans are handing out). We wonder this when we are asked to be hidden under the van to cross the border, when children go to game and we don’t know how to help them, when we are told “I wish I had your blood.“

Reality throws in our faces the irreducibility of our privilege and the difficulty of a real common struggle on the border, as well as the partiality of the material help we provide. But causing even more frustration is the immeasurable asymmetry between us and them, that is, the immense disparity of forces and resources between the states and their military arms on the one hand, and the people on the move and us solidarians on the other. It is such an unequal struggle that it is hard to see a horizon, and often present and future history appear to us as an irreversible defeat.

So why are we here? Perhaps instinctively, because we cannot turn away while our sisters and brothers struggle and die along the borders of Europe. We are here because the contradictions and injustices of this system-world materialize here, because there is suffering and resistance here. We are here to help people cross the borders and continue their journey, mobilizing our privilege and deserting the fortress. We are here because people are hungry and thirsty, and we have food and water. Because people need to wash, and we can bring showers. We are here because we are not going to make revolution by filing reports or cordially knocking on buildings in Brussels, but by self-organizing struggles and conquering autonomy. Because the margin is a place of radical possibility where we want to be, but we will not forget to attack those who conveniently decide on the others from the center. We are here because solidarity and action, not just tired indignation, are our weapons. We are here because they would not want us here, because they would like to bury everything and everyone in the invisibility of these faraway lands or inside the walls of new prisons. We are here because we can no longer leave the border police undisturbed. We are here because we believe that our presence can mean something to the larger “movement” of which we feel part. We are here because here we feel, despite everything, that we really live, that we make sense of our being, that we take part and be part. We are not here for the others but for everyone, even for us, because we want one day to be able to live together in a world of solidarity, without borders and without police. We are here because the time shared around the fire, the real glances and warm words exchanged in all languages, are already a fragment of that borderless world we are fighting for.

We want to be seeds and grains of sand. Seeds of another world and grains of sand in the gears of this system of death. Care and conflict, solidarity and opposition, heterotopia and sabotage are necessary duplicity of a political action that wants to be against being already beyond. To break the dogma of impotence that grips us, to open horizons of possibility. Just as we seem to be undergoing irreversible history, we can still be breaches in the barbed wires of normality.

The machinery of power cannot crush grains of sand, and seeds take root when buried in the good soil.